South Sudanese Transfer Scholar Amou Ajang Featured in VICE

We are pleased to share an article featured in VICE about 2012 Undergraduate Transfer Scholar Amou Ajang. The Columbia University student, set to graduate in 2015, emigrated from South Sudan in 1995. Though she studies political science and international relations, Amou considers herself first and foremost a writer.

This incredible Q&A touches on the violence in South Sudan, life as a refugee, and Amou’s poetry. Amou was featured as a subject in photographer Mike Mellia’s South Sudan-focused portrait series Our Side of the Story.

You can also check out one of Amou’s recent endeavors, A.M.E.N. (Artist Movement Engaging Non Violence), an artistic venture created by Sudanese activist Khalid Kodi.

~~~

Their Side of the South Sudan Story: Amou Ajang, Poet and Student

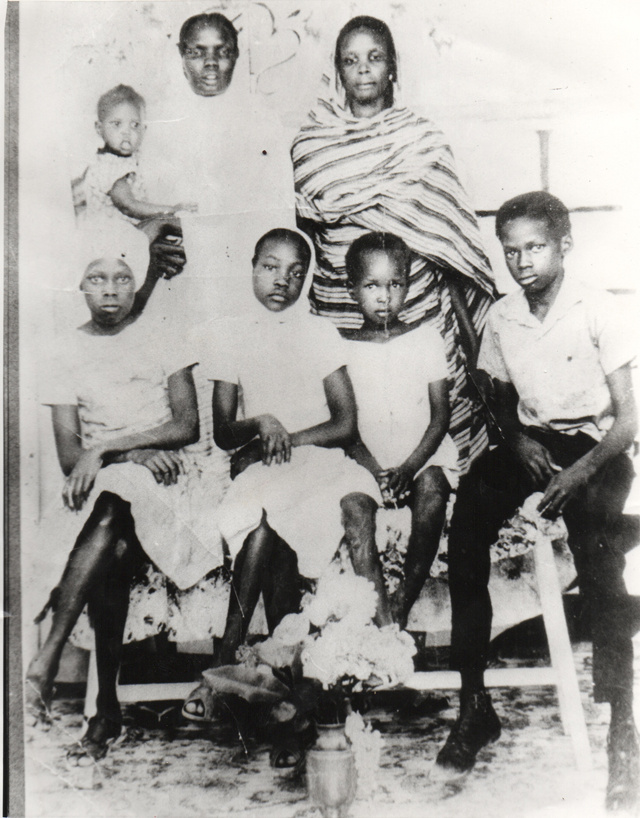

Photo from Mike Mellia’s portrait series Our Side of the Story: South Sudan.

The April issue of VICE includes just one article in its 130 pages. The magazine’s sole story, Saving South Sudan, by Robert Young Pelton, is a gonzo-style dive into the strife of the world’s newest nation, one that has faced perpetual war “with some sporadic days off” since 1955. In April, we received an invitation to a gallery exhibition by New York–based photographer Mike Mellia, whose project, Our Side of The Story: South Sudan, is a series of portraits of South Sudanese refugees turned artists. Subjects included supermodels who’ve walked for the likes of Louis Vuitton and appeared in Kanye West videos, an actor starring in an upcoming Reese Witherspoon movie, and a poet studying at Columbia University. Almost everyone in the series still has family in South Sudan, or a neighboring refugee camp, and many of the subjects’ families don’t know the extent of their current artistic lives.

We got in touch with several of the subjects of Our Side of The Story in hopes of giving them a platform to talk about their almost unbelievable voyages from Sudan to America, from refugee camps to runway shows and top-tier universities. VICE started this series by interviewing model and DJ, Mari “DJ Stiletto” Malek, and today we’re sharing the story of Amou Ajang.

Amou Ajang is a poet, a writer, and a current student at Columbia University. She left South Sudan in 1995 with her family and moved to Arizona, as the climate was similar to what they knew in Sudan. She won the Jack Kent Cooke Transfer Scholarship which gave her the opportunity to begin studying political science/international relations in Manhattan, and is set to graduate in 2015. She told us about pursuing writing and poetry, despite her family’s pressure to study something more practical like medicine, law, or engineering; a website she’s creating to share the art of female “wanderers”; and shared a poem titled “A Cyclical Sacrifice,” which remembers Nuer boys who drowned while trying to swim across the Nile in order to escape the civil war.

VICE: Where in South Sudan were you born?

Amou Ajang: In spite of growing up in Tonj, I was born in Khartoum, Sudan in a family with six children. My sister and father are still in South Sudan today. My parents became refugees in the late 80s. At the time my mother was still a teenager living at home with her family in Tonj, and my father was a young adult studying at Khartoum University. My mother and her older sister decided to leave Tonj due to mass violence similar to that which took place in December of 2013—except at the hands of Arabs and Muslims from the north.

Before she had the opportunity to return to Tonj in 2008, my mother often described her last images of the town as those of burning buildings; the thatched homes of her childhood friends and neighbors crumbling in flames.

Living in Khartoum during the Sudanese civil war was naturally difficult. South Sudanese lived under the constant anxiety of attack, especially as second class citizens. The UNHCR gave my family the opportunity to immigrate to Egypt in 1991, and we took it. I was an infant when we arrived to Egypt, and thus my earliest memories begin there.

Amou’s mother’s family in South Sudan. Her mother is the child sitting to the left of the only boy in the photo.

Tell me something idiosyncratic you remember about life in refugee camps.

I’m very fortunate that I was so young when we arrived to refugee quarters in Egypt. Older members of my family recall details of continued prejudice based on ethnicity and religion. Other than feeling the emotional shifts of the grown-ups around me, at the age of 1-4, I was rarely aware of the tense environment we lived in. I just knew that some days the adults were sad, some days they were stressed or scared, and some days they were angry. However they rarely spoke about it. I remember being curious about why they never seemed to speak about it.

Amou and her family reuniting re-united for the first time in 1999.

Do you consider yourself an artist?

I consider myself a writer. Growing up in my household, saying that you were a writer or an artist was the equivalent of saying that you are an aroma therapist at your core (which, let’s be honest, is valid in its own right). My parents pushed my siblings and I towards certain career paths (medicine, law, engineering), because they wanted us to have an opportunity to escape the instability that we lived as refugees. However, the older I get, the more I am haunted by the desire to write. I can no longer ignore the calling.

I create poems as a part of my daily life, and at times the process is almost thoughtless. I will open my phone and start writing notes, usually on life, an event, a frustration, a love, a pleasure, and then I will look later and think, oh that’s a poem. Other times it take the process is longer. Recently, I wrote a personal essay titled “Cyclical Sacrifice,” and decided to take the same concept to create a poem from it. I wrote the poem over a period of four hours, from 11pm-3am, last winter. It’s about South Sudan and is still a work in progress.

A Cyclical Sacrifice

A love short lived, a brief passion

His memory warm, hurried, almost imagined

Invited to pre-mature rest/ his death? Consent-less

But he came back in a dream

toothless, smooth, ebony, full of light

swollen cheeks, deep dimples, small clasp, full of might

eager with that stupid gayety that accompanies a youthful laugh–

he smelled faintly of tenderness, he smelled faintly of new life

His name was Tong, or was it Riak, or was it Madut, or maybe Akech,

recalling the war for which his father fought, but from which he did not escape?

He came as brief solace, to a lonely woman in a world of few pleasures… but yet again…

a life short lived, just eleven

Equipped for war— textured coal completion

Invited to premature rest, he too, consent-less

He haunted her dreams…

Toothless, ebony, firm, cold of as ice

Swollen cheeks, deep dimples, empty clasp, devoid of life

She raised him to a concave breast, where stiff curved lips would not latch

He smelled faintly of new death and faintly of new strife

And so it felt as if her world wanted her to be raw and lifeless

Tempted by the prodding of wise-men whose very kindness it had devoured to

a boney carcass

In a traditional fashion

Textured coal complexion, geometric patterns,

Consent-less

hot blood flows,

Belonging to black baby lambs, a cyclical sacrifice,

Consent-less

And so it felt like her world was tempting her to become one of them.

A world of sharp ivory prongs

Grey shriveled flesh, smelling faintly of death

of swinging butchers to chubby hopes, chopping swollen lovelies

Bludgeoning them down to blunt nothing’s

Sloppy forgettable

empty used to Bes

bludgeoning them into uselessness, that they too might join the lifeless

Amou Ajang

Tell me something personal you’ve heard or witnessed in South Sudan that illustrates the current issues the country is facing.

My father and little sister live in our family home in Juba. During the first days of fighting two Nuer boys, our neighbors, came to our door. My family hid them for a few days. Those boys survived but I am told that their sister went missing and she still hasn’t been found. My family still doesn’t know what happened to her. We can only imagine what kind of horrible end she met. There are no words to describe how empty I feel when I think about the violence that has occurred on our soil for so long, but most specifically, the violence against women and children.

Another story that struck me came from an old friend over Christmas break. He is from Bor, one of the areas heavily hit with violence. He told me that the young bodies of children could be seen floating on the Nile River. Some children tried to swim across the river to get away from the fighting and drowned. I never saw pictures, but its an image that is very difficult to get out of my mind. My poem is dedicated to these children of war.

A photo Amou took at the memorial of former rebel leader, John Garang.

What upcoming projects do you have? Anything related to raising awareness about Sudan?

One of my favorite Artists is Khalid Kodi, a Sudanese activist, artist and professor. During the Sudanese Civil War he and his wife Nada Mustafa Ali (a researcher, professor, and activist) raised awareness of the plight of the Southern citizens. I’ve been lucky enough to be recruited on to one of his projects for Healing and Peace. In 2012 he started Artist Movement Engaging Non Violence (A.M.E.N.) in response to the burning of public places of worship by Muslim radicals in Sudan. The temple was significant because Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, essentially people of all faiths, gathered there to worship. To show solidarity, he enlisted several students to create religious paintings as gifts to the church.

Depending on our ability to find funders and collaborators, we hope to travel to Sudan and South Sudan within the next year, showcasing the works, and finally delivering them to their destination, the reconstructed house of worship. Alongside this traveling gallery, we hope to provide artistic workshops to promote this idea of healing through expression. There are several other phases of the project that we would like to realize, but for now we are looking for collaborators and support.

The pieces are magnificent, and will be displayed at Boston College in October. For more information, check out the Facebook page.

Since many of my poems have a strong component of the wandering woman, I might call my first collection Women Don’t Wander. (“Nyiir Accie Hou” in Dinka, my mother knows what this is about). It’s scary, you know—going from self-identifying as an artist in private, to sharing your work publicly. But it’s exciting at the same time, like a first boyfriend.

What will it take to end the violence?

There are many barriers to overcome because the violence is cyclical, permeating all aspects of our society, both in the diaspora and back home. A structural remedy to political and tribal violence begins within the ruling elite Dinka and Nuer, who compose most of the ruling party and are not only known for their regality, but also for their tempers and stubbornness. We tend to be ambivalent towards new concepts and perceive change as threatening to our customs (which if we are honest, could use change because they have historically benefited certain groups over others).

I think it is new ideas that we need in order to see true peace. We have to make room for a new generation of leaders. This is not to say that we must completely dismiss those who have served our country since before independence, but the fresh ideas of several educated experts that we have at our disposal need to be allowed to penetrate the current system. It seems as if most of the current political positions are held by elite members of the SPLA, who reshuffle themselves every few years/months. It’s important to add diversity of thought and process by adding new faces and giving them actual power. This will break up the power struggle within the party that is becoming nearly ancient.

What do I mean when I say that the violence is cyclical?

A similar violence broke out in 1991 within the party during the Sudanese Civil War between the Khartoum Regime and Southern rebels. Just like what happened last December, a rupture within the party led to widespread Dinka murders at the hands of Nuer militia, and pushed back peace for all 64 tribes. New faces will break this cycle.

As an artist, I believe that healing can come through expression. Many of us, from the civilians back home, to the lost boys and girls, to the new generation of South Sudanese in the diaspora, carry pain, trauma, tension and confusion; essentially, we carry an internal violence. The fact that we are rarely speak about these things leads to broken homes, to our youth acting out, to an increase in high school dropouts, not to mention the prolonged suffering from mental illness due to stigma. We need more people to stand up and speak out against the concept of that “which we do not speak of” that we seem so committed to as a people. Through merely talking about these things, or expressing ourselves creatively, we create healthy outlets and increase the numbers of successful and functional members of our communities.

In addition, we foster community and build connections. If I write a poem, and Khalid paints a painting, or South Sudanese pop artist Yaba Angeleso writes a song—these expressions are not only personally cathartic, but they allow us to connect, illuminating the fact that in our human experience, we are all much more similar than we are different.

Find out more about Mike Mellia’s South Sudan–focused portrait series, Our Side of the Story, on his website.

Follow Zach Sokol on Twitter.